Shéshān to Guăigùn: 76 year old Lao Zhang and his “guăigùn form”

/DREAM COME TRUE: Shéshān to Guăigùn Almanzo “Lao Ma” Lamoureux

PART II: 76 YEAR OLD LAO ZHANG and his “GUĂIGÙN FORM”

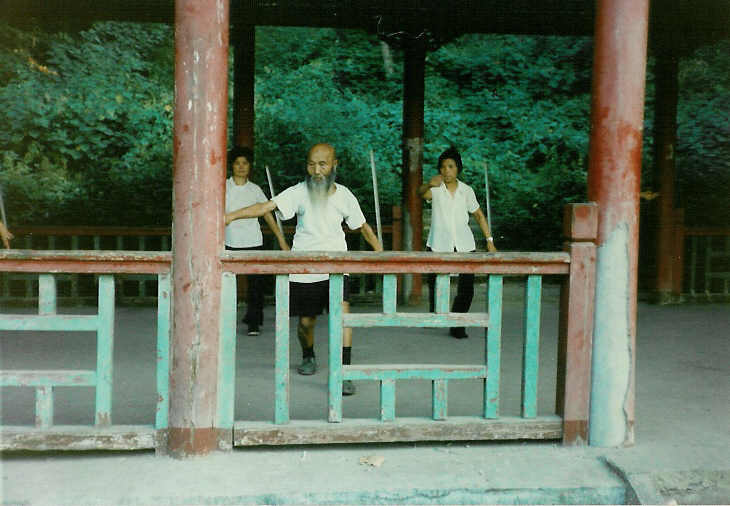

Lao Zhang was a long-time student of YéYe and beloved by everyone in this mountain martial arts community, 30 years my senior and a deaf mute. It was the only time in my life I ever studied -- anything! -- from a disabled teacher. Because my spoken and listening skills of the Chinese language were rudimentary at best my classmates referred to us as two “no speak men!” But he did not consider himself disabled. When confronted with questions he would grab a rock outside the pavilion and scratch out Chinese characters on the cement floor to answer questions. The students actually understood his grunts and other-worldly sounds as well, to my utter amazement! When he would write a clarification down for me personally he would get up, nod satisfactory, point to the inscription on the floor, then look at me with an astounded expression and proclaim to everyone else, “You laugh at me, pointing to himself then pointing at me shouting, HE can’t talk, understand, READ or WRITE!!” He was hard for me to understand, but I was treated more like a talking monkey and object of comic relief, so I simply sat back and enjoyed his teaching and his humor. He was such a lot of fun too in addition to everything else he was! It was the most wonderful, gratifying and humbling experience of a 3 year magical mystery tour that will stay with me until the day I die; the studying of Guăigùn, in Wŭchāng, on Shéshān from Lao Zhang in the summer of 1986!

The Weapon Form called Guăigùn, composed of two characters, guăi (枴) meaning walking cane with hook (implied), and gùn (棍) referring to stick or cudgel, is a unique weapon. There are other Chinese names for Cane Forms, gùn zi (棍 子), guăi zhang (枴 杖), and, of course, guăi gùn, to name three. The first refers to Stick Forms, the second to knob or decorative handles, the last to a Hooked Walking Stick, which is the one I know as a weapon and a Form.

Guăigùn can be carried anywhere at any time, without causing alarm from the public or authorities, as formidable a weapon as it really is, even onto an airplane, at the height of 9/11 hysteria! Or into a courthouse or police station. You can carry it about, and it has a myriad of practical uses. For sure you cannot carry a sword, Jiàn (劍), neither straight or curved broadsword, Dāo (刀), in such manner, and practical uses of sharp metal instruments are limited. But not a walking cane. And the Form itself was unusual, like Drunken Forms or Monkey Forms, there is an element of theatre inserted into the Form at its beginning and ending.

Guăigùn has all the techniques of metal-edged sharpened weapons: chop straight down, at angles, thrust, poke, throw, punch with hilt, etc. What it has that makes it unique and effective is the hook. The hook is primarily used to capture, hold and manipulate extremities at the wrist and elbow joints, and apply Qínná (擒 拿) or grappling joint-locking submission holds. With a larger hook, neck, upper arms, fore arms and legs can be locked, held and manipulated as well.

I learned a stick form from the school of Master T.T. Liang, through his disciple Paul Gallagher, many years before the Guăigùn and Lao Zhang. He called it Cane Form, meaning I believe a knob-headed stick, or the rattan weapon favored by Indian police with the 4 ft short staff, and with officers the hooked walking cane. Both are rattan. I do know that Mr Liang’s particular weapon Form originated as a Praying Mantis broadsword and he transformed into a stick Form. But it is not a hooked walking stick. It always amuses me to see his Form or similar ones demonstrated using a hooked cane (the internet is crammed with them!) and there is absolutely no manipulation of the hook and its end of the weapon...otherwise the Cane Form learned from Lao Zhang is just full of martial art weapon styles, and techniques learned prior to Guăigùn study can be modified and brought to use with hooked cane training, or if not known before another style, Qínná for instance, can be pursued separately and then brought back to enhance Guăigùn Form understanding and depth of use.

At any rate this is a beautiful, satisfying Weapon Form, that like all weapons projects your intent, qì (氣), what have you, away some 3 ft. from your body into an opponent or partner in two-person interactive work! And, you never know, the Cane Form might come in handy someday. I have deterred people approaching me in parking lots with little more than loud shouts and pointing the cane at them in a strong gōngbù (弓 步) stance. It was all I needed to turn them around to flee in the opposite direction, whatever their purpose of advancing on me in a threatening way was in the first place. Also, recently I went to a movie with brother Dr Jay Dunbar, also a recipient of Lao Zhang’s Guăigùn through my tutelage. Being a good student he had his cane, I had one of mine and we immediately began a correction session right there in the lobby between movies. Having a great time and oblivious to all, we seemed not to bother other cinema patrons or cause any concern — of course Southern Village is a high-end, laid back planned creation, but we would have caused more confusion and alarm, I’m sure, if we were packing hand guns, open and carry!

Lastly, as alluded to above, there is a fun aspect and theatre associated with Guăigùn. Chinese Stage Opera, an art form in itself, employs Chinese Martial Art techniques and Forms as strong, integral components of the stage production. Many bits of humorous theatre are associated with various Hand and Weapon Forms, much like the humor of the old swashbuckling sword play in mid-nineteenth century Errol Flynn movies. Unfortunately for many Western adoptees of Asian Arts, this component gets lost and the more serious attitudes dominate Form demonstrations. As mentioned, these occur with Drunken Forms, Monkey Styles, Rope Dart, and large Máobĭ (毛 筆) (writing brush) Forms, to name but a few. In China, we began training Guăigùn by miming old people, bent over, struggling with shopping bags and a hooked walking stick, let’s say walking thru a park. The seemingly vulnerable, venerable ones detect a threatening presence, a youth gang perhaps, they slow down even more, cautiously look around, set down their shopping bags...and then!! BOOM! The Form begins! The bent over old ones, like human transformers slowly straighten up, morph into super action heroes, go into the Form postures at a bit more vigorous pace than the shuffling grandfolks coming home with mesh bags full of eggs and bok choy! They proceed to lay low the hoodlums one by one. At the Form’s conclusion they smile, look around very pleased and contented, slap the dust off their hands and pick up their bags, with maybe a wack or two at a couple of prostrate thugs, and shuffle off home! This part of the Form always draws an enthusiastic reception from Chinese audiences in China and even in tournaments here in Jīnshān (金 山), Gold Mountain. In fact, it could be the main reason I placed 1st in my second outdoor Regional Tournament in Wŭchāng District (the first tournament I participated in was an indoor Provincial-wide event) performing Guăigùn to an energized audience! Actually, I believe it was more attributed to the fact that I trained to the tournament rules and time limits, the runner-up 2nd Place with 9-linked belt, a teacher of Wŭshù in Wuhan Opera, and of much higher skill and rank than I, came in way under time and was placed second (both of our trophies were an orange/white, rectangular pillow towel with Shanghai written in English cursive script, a highly sought after acquisition circa 1987!)

For the theatre aspect, Lao Zhang taught us to adopt various walking gaits in the Form’s beginning and ending sequences. Men had one of two walks; “Old Man” bent over, with a slow, staggering, lurching gait. The other a “Scholar’s Amble” which recreates a slow, straight-back, measured, dignified amble with frequent pauses where the scholar applies a couple measured strokes to his long white beard as he gazes around. The women assumed the mincing walk of an old matron in bound feet by walking on their heels in short, sharp steps. A truly impressive weapon Form that was super enjoyable to learn with the added theatrical humor thrown in, remains the same in each and every reenactment, and has long been, since my return from my “Dream Come True” China sojourn, my signature Martial Art Form!

If you are planning on training with Guăigùn please enjoy your immersion. Work hard, do good, and carry your Guăigùn/Hooked Walking Cane out on a stroll, “to Terror of the Public,” without anyone knowing you are fully armed...and dangerous!

GLOSSARY OF Chinese Characters Used in the Text

Tàijíquán (太 極 拳). Great Ultimate Extremes Fist. Refers to Internal Martial Art

Tàijí (太 極). Great Ultimate Extremes. Refers to many endeavors other than Martial Art

Wŭshù (武 術). Chinese Martial Art (In Taiwan, the term used is Kuoshù)

Grandfather Dīng,” (丁 爺 爺)

Táng Pài (唐 派). Táng System of Martial Art, developed by the first Táng Emperor’s third son, Tangbi

Guăigùn (枴 棍). Hooked Walking Cane

Shéshān (蛇 山). Snake Mountain. Shān can refer to different sized mountains. We might not call the one in Wŭchāng a mountain but a hill, but in China they are all “shān”

Guăi (枴). Walking cane with hook

Gùn (棍). Stick or cudgel

Gùn zi (棍 子). Rod or stick

Guăi zhang (枴 杖). Walking stick

Jiàn (劍). Sword

Dāo (刀). Broadsword

Qínná (擒 拿). A twisting, grappling form of defense involving the capture and manipulation of the joints

Qì (氣). Vital energy, breath energy

Gōngbù (弓 步). Bow stance, the #1 stance of Tàijíquán

Máobĭ (毛 筆). Writing brush

Jīnshān (金 山). Gold Mountain (America). Mĕi Guó is the official name for America (“Beautiful Country”). Jīnshān is what many Chinese people call the U.S., perhaps traced to the California Gold Rush and/or building the Trans Continental Rail Road through the Rockies from the West Coast. Both events drew Chinese workers in large numbers to the U.S.

blackbamboopavilion@gmail.com

http://www.blackbamboopavilion.com/